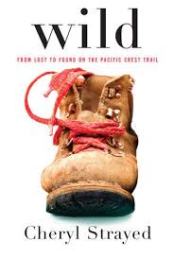

Wow, it’s been a long time since I’ve written anything here. The past semester nearly drowned me, and although I’ve been reading, I haven’t been writing anything that hasn’t been absolutely required of me in order not to make a terrible fool of myself (and then, I may have done that anyway). As is somewhat usual by now, my world is a precariously balanced set of items – work, money, family, among others – that I have so far put together in such a way that they have not collapsed (yay, me!) but could, it seems, do so at any moment. I’m in the middle of another uncertain (perhaps doomed) academic job cycle and the future looks fairly dim. There’s a little pinprick of light out there, but it’s far away and I know I can’t count on it. I wouldn’t in any way compare my current situation to the grieving, drug-addled Cheryl Strayed of her memoir Wild, but let’s just say the book resonated with me particularly well at the moment. As I scroll constantly though a list of both sane and crazy options in the event that I don’t get a permanent position, I’ve added “Hike the Pacific Crest Trail” to my list, although I’ve thus far avoided thinking about the damning logistics of doing so with a young family. Probably not going to happen. Nonetheless, sometimes the idea gives me a little glimmer of hope, or just makes me smile.

Wow, it’s been a long time since I’ve written anything here. The past semester nearly drowned me, and although I’ve been reading, I haven’t been writing anything that hasn’t been absolutely required of me in order not to make a terrible fool of myself (and then, I may have done that anyway). As is somewhat usual by now, my world is a precariously balanced set of items – work, money, family, among others – that I have so far put together in such a way that they have not collapsed (yay, me!) but could, it seems, do so at any moment. I’m in the middle of another uncertain (perhaps doomed) academic job cycle and the future looks fairly dim. There’s a little pinprick of light out there, but it’s far away and I know I can’t count on it. I wouldn’t in any way compare my current situation to the grieving, drug-addled Cheryl Strayed of her memoir Wild, but let’s just say the book resonated with me particularly well at the moment. As I scroll constantly though a list of both sane and crazy options in the event that I don’t get a permanent position, I’ve added “Hike the Pacific Crest Trail” to my list, although I’ve thus far avoided thinking about the damning logistics of doing so with a young family. Probably not going to happen. Nonetheless, sometimes the idea gives me a little glimmer of hope, or just makes me smile.

Strayed has a great story, but so many things about this book could have gone wrong: it could easily have veered into sentimentality, self-help platitudinousness (this has to be a word, right?), or hectoring. But Strayed is a really good writer, and she keeps it simple, mostly allowing the reader to draw his or her own conclusions/life lessons/caveats from the situations she describes, avoiding many common pitfalls of a memoir of this type. This is probably also why the book has been extremely popular, and why I found it resonated with me: although her situation is unique and her solution extreme, there is a certain universality of emotion and response described in the book. I might be facing a different set of problems than she did, and I might not decide to solve them by dropping everything and unadvisedly hiking the Pacific Crest Trail with no preparation, but I’ve certainly felt whatever sense of grief and abandon that leads her down that path, and the idea (as noted above) certainly sounds tempting. In other words, Strayed does a good job of allowing me (or you, or anyone) license to both feel the extremity of whatever it is that’s on our minds or in our hearts and follow that to its logical conclusion. She doesn’t allegorize her story, but she offers it as an allegory to you. Make of it what you will. I appreciated the opportunity to escape into my own fantasies about living on houseboats or moving to a country whose language I don’t speak or disappearing onto the PCT.

I won’t give away all the details of the story here, but Strayed, having lost her mother and gotten divorced within the space of a year and at an age when most people are thinking about graduate school, not marriage (much less divorce) or death, does a lot of stupid things and then decides, with the kind of clear thinking we expect from a grieving, possibly drug-addicted, immature person, to hike a good portion of the PCT, a wilderness trail that runs from the Mexican border to the Canadian, through California, Oregon, and Washington. Unfortunately, she’s never even really camped before, much less backpacked hundreds of miles on her own. Despite her ill-considered decision (which she regrets within the first ten miles), she sticks with it, more or less, figuring out along the way how to do the things she doesn’t know how to do and making alterations to her route when it is proves impassable. It’s not really a traditional tale of stick-to-itiveness or goal achievement, which is both the essence of the story and the source of its appeal. If she executed her plan perfectly and emerged whole and healed from the experience everyone would smell a rat, despise her, and hate the book. Instead, she mostly accomplishes what she set out to do, not quite in the way she set out to do it, and ends up in a better, but by no means perfect, place at the end.

Maybe the kind of messy reality the book winds up with is another source of my personal resonance with Strayed’s story. Of course, I haven’t quite ended up where I thought I would, in senses large or small. I’ll leave aside the bigger issues for now, but certainly as regards this blog I have no illusions that I will accomplish my goal by my birthday, which is now a few weeks away. I really did think that it was an achievable mark, 40 books in a year, and maybe in another year it would have been. I’m not giving up; I’ll try to post on as many books as I can before the 25th, but I’m not going to delude myself or chastise myself about my prospects. I probably am not going to do what I set out to do, but I did what I could and at this point that has to be enough (I’ve been working on applying this principle to my professional life for years and I’ve been less successful; maybe this will help). I do plan to keep the blog going, and I hope people will continue to read it. I’m going to try not to beat myself up about it or call it a failure. Rather, I’ll take what feels like a success – writing about what I want, sharing it with people, reading more books and thinking seriously about them – and leave everything else. Part of Wild was about achieving tremendous goals, but an equally important part was about keeping those goals within the realm of the possible, or even the probable. And that’s what I’ll take with me into the new year.